Army

Army

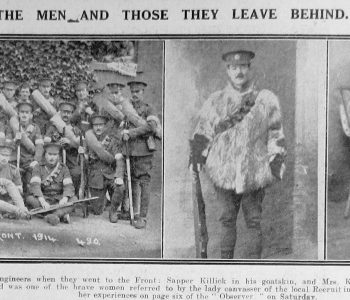

Killick, Unknown First Name

Sapper Killick

Rank: Sapper

Regiment: Royal Engineers

Wife: Mrs Killick

Address: 37 Stonefield Road, Hastings

Other Info: Article text reads: “The above pictures show a group of local Engineers when they went to the Front. Sapper Killick in his goatskin, and Mrs Killick at home with her four little children. … and was one of the brave women referred to by the lady canvasser of the local Recruiting Committee in her interesting account of her experiences on page six of the ‘Observer’ on Saturday.”

The article in the Hastings Observer dated Saturday 1st May 1915 is titled:

‘The People’s Patriotism – a Lady Canvasser’s Experience’

It reads as follows:

‘My note of last week on the wonderful patriotism of the people, as shown by the experiences of the Hastings and St Leonards canvassers, has induced a lady who has been engaged in this work to write the following account of some of the incidents which came under her notice. I give the letter exactly as it was written, but it should be explained that although the statements in it are true, the names and other particulars have been altered to avoid the causing of any possible suffering by the people concerned in the incidents. The lady, after remarking that she thought I might like to know some of her experiences as a Recruiting Canvasser, proceeds as follows: –

“I could write volumes on the heroism of the brave lads who have gone, and the wonderful patriotism of the women left behind. I could also say a great deal about the sweetness of these same dear women who have given their best beloved to fight, and in some cases to die, for their King and Country.

To visit these homes is an education; one sees humanity in a form to which one is quite unaccustomed. It is an experience which I shall always be glad to have had and I am proud of having been allowed to go through it.

At the beginning of this terrible struggle no doubt many young men joined the war light heartedly, thinking perhaps the War would be over soon, and that they would ‘see like’, but the young men who are joining now are fully aware of the gravity of our position in this war, and are going prepared to give their lives if necessary to free their dear country from the menace which threatens it. I have even had mothers say to me: ‘I don’t expect to see my son again, but he had to go; it was his duty!’. No moaning about these brave women!

An only son, a lad just 18, whose mother told me was ‘the best boy who ever lived’ said: ‘Mother, I’m going out to fight, and I hope to come back: I want to give you a little parting gift; I thought you’d like this; you can always wear it.’ The gift was a soldier’s button, gilded and made into a locket, containing his portrait, and threaded on a gold chain, and the message with it was: ‘The heard that this locket lies on I hope will never ache for me’. No wonder that mother was so proud! I said to this dear woman ‘Are you glad your son offered himself? She replied ‘Yes, it nearly broke my heart, but I would rather my son was killed than he should stand aside when his country so sorely needs him’. Truly a splendid feeling when expressed by a simple kindly woman who so evidently worships her boy.

The mothers and their sons and husbands

Almost at the next house I called at there was a pretty frail little woman, with four children, their ages ranging from one to four years. I asked the usual question and was told her husband was serving. Seeing these babies, I asked her why her man had gone. She said ‘Madam, my husband (text unclear) good work to go; he joined after the Germans had treated the Belgians so badly. He came home one night, and he said to me ‘My dear, I must go out and fight, so that you and my children shall not be treated as the women and children of Belgium have been treated!’. I said: ‘How fine of him!’ She replied: ‘Yes, he’s a fine man is my man.’ and the world of pride and tenderness put into those words I shall never forget. Before I left she added: ‘He’s only doing the right thing’.

The next house was a home from which all of the sons had joined the Colours, four in all. I said to the mother: ‘All four boys have gone then?’ She replied: ‘Yes, Ma’am, and if I had ten they should all go!’. There is humour too, sometimes, for instance, when the mothers have so many children they cannot remember all their names, and they call out to a daughter at the back ‘Lizzie, what’s Charles’ other name?’ and invariably a neighbour who has just popped in gives the required information, whilst the mother apologises and says ‘I can never remember all their names!’

Another case I enquired into the mother told me she didn’t want her son to go as he was the only one she had. She thought families which she knew of ought to have sent some of their sons, so she said to her by she would never consent to him joining. The lad replied: ‘Mother, I shall go whatever you say, because I must; I can’t stick back. I’m young and strong, but you would make me happy if you would say you would let me go.’ After a few days persuasion the boy had his way. I said to that mother, ‘You wouldn’t have had him hold back would you?’ She said most emphatically ‘No! I would not; I know it’s his duty.’

At another house where I called there was the wife of a sailor, and she kindly told me her husband was in action in the Dardanelles. When I remarked; ‘You naturally feel anxious.’ She said, ‘Yes, a little bit, but my man loves a fight!’. And I believe, from what I’ve heard during my canvass, that most sailors do.

Under age but serving

One meets with many cases of widowed mothers who have parted with loved sons. I talked with one whose only son, 21 years old, had joined. He had never previously left home, and the mother said, and she added: ‘I’m proud of him, very proud, but how I shall miss him, my dear boy; I dare not think about it, and how I shall cry when he goes, but I shan’t let him see, you know.’ Dear, unselfish creature. Again, an only son of a widow, ‘I shall miss him, yes, no body knows how much, but I’m not the only one, and mothers mustn’t stand in their boys’ light nowadays.’

The keenness of the lads to get to the fighting line is frequently shown. Here is one true narrative. A mother told me her boy was bent on getting out, but he was only just over seventeen. At the recruiting office the following conversation took place: – Recruiting Officer: What is your age? The boy: Seventeen, sir. Recruiting Officer: You must be 19. The boy: Very well, then, I am 19. The mother added: ‘And he has gone; and now my other son, who is not quite 16, is jealous, and says he means to get in somehow.’

Soldiers’ mothers’ indignation

The Kaiser is considered a very evil person; in fact, one woman told me she thought the devil was set loose on earth in the shape of the Kaiser. I would like to tell you sir, of the indignation of these mothers and wives of soldiers at the difference of the treatment of British and German prisoners of war. Their indignation and anger are only equalled by their superb patriotism.

The demand for Compulsory Service

I would like to say that wherever I have been – and I have called on some hundreds up to now – I have found a strong demand for compulsory service, and complaint of the unfairness of the voluntary system. Even the men who have not gone, or, at least, some of them, say they think compulsory service should be introduced. As to the unfairness of the voluntary system, I will give one instance out of many. At one house at which I called there were three men of military age: they not only refused to go, but would not even give their names, and seemed to be delighted at their astuteness in preventing me from obtaining the information I wanted.

In the next house there was a woman with a child. Her husband had given up a good berth to enlist, and naturally she felt that the young men next door should not be allowed to stay back. Another phase of the unfairness of the system, and one which struck me more forcibly, is the unwarrantable sneering by neighbours at men who have not gone, and are apparently strong and robust, but in reality physically unfit. On one case of this kind need be mentioned.

In one road several women told me that at a certain house there was a man who ought to go, but his wife would not let him. On making enquiries, I found that this poor man was suffering from heart disease, and he had been under the doctor for six months. The wife said to me: ‘If he had been fit, he would have gone long ago, and I only wish I could take his place!’. To my fellow women, therefore, I would say: ‘You have shown your own courage by letting your men folk go, don’t be too ready to sneer at your neighbours; one never knows the skeleton in the other person’s cupboard.

Soldiers’ parents and misguided reconciliation advocates

Just a word to the misguided people who want reconciliation, and are asking us not to punish or humiliate the Germans. Let them call, as I have done, at the houses of the mother and fathers of the brave lads who are fighting and dying for their country, and have written home describing the vile deeds of the Germans they have witnessed in Belgium and France. Any talk of friendliness towards Germans makes these parents boil with rage. The view most of them take is that their sons’ and husbands’ lives are being wasted if we are to become reconciled to the Germans for their misdeeds, and making it impossible for Germany ever again to bring about such a slaughter of innocents.

Only one insult

In conclusion, I would like to say I have had many invitations to re-visit the homes where I have called, and only once have I received an insult, and that was from a widow with an only son. I can forgive her, poor soul; her bark was probably far worse than her bite, for I have no doubt that in her heart she wants her boy to do the right thing.”

Published: May 1915

Please use the comments box below if you can provide more information about this person.

Thomas R Blick

Thomas R Blick

C Dawson

C Dawson

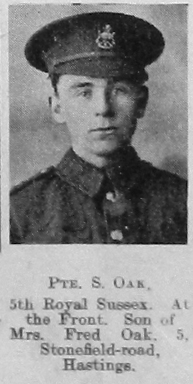

Sidney Oak

Sidney Oak

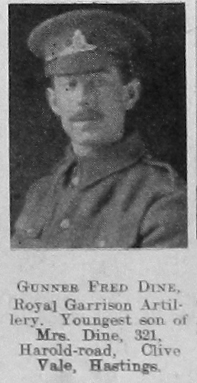

Fred A Dine

Fred A Dine