Navy

Navy

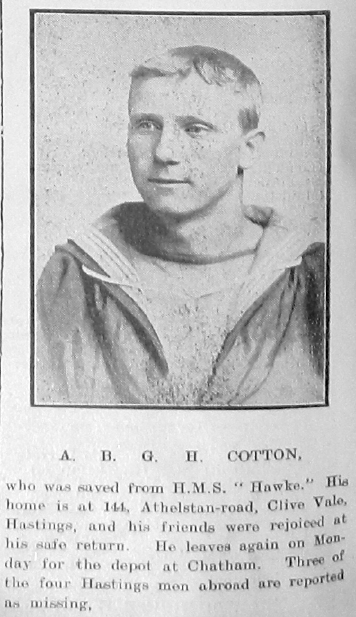

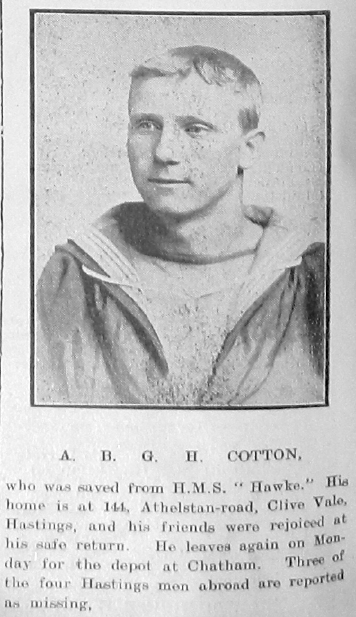

Cotton, George Henry

George Henry Cotton

George Henry Cotton

Rank: Able Seaman

Ship: HMS Hawke

Address: 144 Athelstan Road, Clive Vale, Hastings

Other Info: Was one of 70 survivors from a crew of 594 aboard HMS Hawke when it was sunk by German submarine U9 on 15th October 1914. His friends rejoiced at his safe return. He leaves again for the depot at Chatham.

An article in the Hastings & St Leonards Observer dated 24th October 1914 reports: “George Henry Cotton, of 144 Athelstan Road, Clive Vale, was one of the survivors of the ill-fated cruiser ‘Hawke’.

He is a man of 19 years’ experience; he came out of the Navy under the good conduct scheme in March 1906, and was called up as a member of the Royal Fleet Reserve at the beginning of August. He left Hastings on Bank Holiday, and after being at Chatham for a short time he embarked from Queenstown on the ‘Hawke’. In the North Sea the Hawke did patrol duty for several weeks. On board the ‘Hawke’ were three other Hastings men; Fred Foster (a petty officer of the Naval Volunteers), Crouch and Bevis. *

Mr Cotton, in an interview, said he saw all three of his fellow townsmen on the fatal Thursday morning just before Church, between 10 and 11 o’clock. They picked up a mail from another ship, and the letters were taken to the mess deck for distribution. Cotton was with the ‘captain of the top’ (a Petty Officer), and came up on deck with water to clean paint work. He was standing in the midship part of the craft on the port side, when suddenly there was an awful explosion.

“I looked around”, continued Cotton, “but I could see nothing but coal dust coming up through the ash hoist. I guessed what was up alright – I knew we had been torpedoed. The next thing I remember is that the bugler sounded ‘Still’ which meant that every man should wait and await orders. The Captain stood on the bridge, and I heard him give the order: ‘Out Boats’. The ship was then listing very badly. Then came the order, ‘Hands, save yourselves’. As a member of one of the boarding boats crew, I took my proper place; the crew got into the boat, bar two, and the order was given to lower. This was a matter of great difficulty, as the ship had listed so much that it was almost impossible to lower the boat. However, we lowered her to the waters edge, and the foremost fall of the boat became jammed (in contact with the ship’s side). We unhooked the after fall all right, but the foremost fall hung up; it would not unhook, and whilst the stern of the boat was down towards the water, the bow hung up in the air. The bow was resting on a bolt or socket. Eventually the boat fell down five or six feet into the water. Then I should think at least ten men jumped clean into the boat from the ship, and others missed.

We had to move away to prevent from being swamped. We got out oars, and pushed away from the ship and pulled to her stern. Fortunately the sea was calm. We picked up several hands, we rowed away a short distance to see if we could take any more. We thought we could take a few more, and did so, making a total of 49. The ‘Hawke’ was now right over on her side, and the masts almost in the water.

The cries of the poor fellows going down with the ship were dreadful, and of course I shall never forget them. The Gunner (Mr Dennis) took command of our boat. We saw the ‘Hawke’ disappear. Our boat had a hole on the starboard side, one of the planks being split, and we had to keep bailing for five hours. On leaving the scene of the disaster we went first north, then north-west and then to the southward in the hope of getting into the track of vessels.”

Asked if the crew saw the submarine which did the mischief, Cotton said: “Oh yes, and she followed our boat for hours, and was within 150 yards at the time. We pulled with all our might. After four hours we saw smoke, and then a ship’s mast and funnels. We pulled towards her, and she approached us. We fired three rockets. The craft proved to be a Norwegian steamer. The wind had now freshened, and the sea was getting rough. When we got alongside we laid on our oars; the Gunner shouted: “We are a shipwrecked crew, will you take us aboard?”. The captain replied “Yes, certainly”. We all got safely on board, and tied our boat to the stern of the Norwegian. (The captain was Mr Isak Swedswig, and the ship Indesta. Read more at wrecksite: https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?62228)

The captain and crew treated us very kindly; we were very cold, and the captain gave each of us a thimble glass of whisky. The Norwegian craft steamed back to somewhere about the spot that the ‘Hawke’ went down, but there was no wreckage or anything to be seen. One of my mess mates went up to the ship’s masts to see whether anything was coming along. He sighted the German submarine, which continued to follow us to dusk, no doubt in the hope that one of our cruisers would come to our help, and that they would be able to serve her like they served the ‘Hawke’.

We turned back and steamed towards Aberdeen, and came across the trawler, the ‘Bevy Rennis’ of Aberdeen; the captain agreed to take us on board, and we left the Norwegian. We were splendidly treated both in the Norwegian ship and the trawler.

It was a 25 miles journey to Aberdeen, but we got there safely before daylight, and were landed about half past six. I cannot speak too highly of the kindness we received on both crafts; they gave us the best of everything they had, boiled us fish, made us hot tea, and dried our clothes. At Aberdeen we went to the Sailor’s Home. Captain Layard, of Aberdeen, visited us early, and brought a supply of tobacco, cigarettes, and pipes, and were were given clothing. As soon as possible, at nine o’clock, on permission being given, all the survivors telegraphed to their friends; naturally I was anxious to let my wife at Clive Vale know I was safe. We remained at Aberdeen till Saturday morning, then we caught the train for Chatham”.

Cotton further stated that the ‘Hawke’ sank in 70 fathoms of water and added: “If we had not been picked up by the Norwegian our boat must have been swamped, and we should have been drowned as the sea came up very rough.” Cotton, who now wears the cap of HMS Pembroke, Chatham Depot, is enjoying a deserved week’s leave of absence.

* Bertram Kirkby of Hastings was also lost on HMS Hawke.

Published: October 1914

Please use the comments box below if you can provide more information about this person.